Signs of Life

As a teenager, Michelle Litchman was often called upon by Deaf family members to join them at doctors’ appointments and interpret medical advice. When she went into health care, she saw an opportunity to give Deaf patients a stronger voice.

By: Maureen Harmon

Illustrations by: Peter Arkle

Photo by: Kristan Jacobsen

Tamiko Rafeek spent months feeling tired and sick and, at one point, became concerned enough that she headed to her local emergency department. She knew answers could be found there, but when she arrived, she realized no one there was capable of communicating the answers to her—a Deaf woman in need of medical care.

Upon being admitted to the ED, Rafeek was told that there wasn’t an interpreter available. She tried to read lips from her hospital bed and understand why she was being given shots every three hours, why the tests doctors were performing were so painful, and why she was asked to stay overnight. But lipreading proved useless—there was just too much medical jargon with which she was unfamiliar.

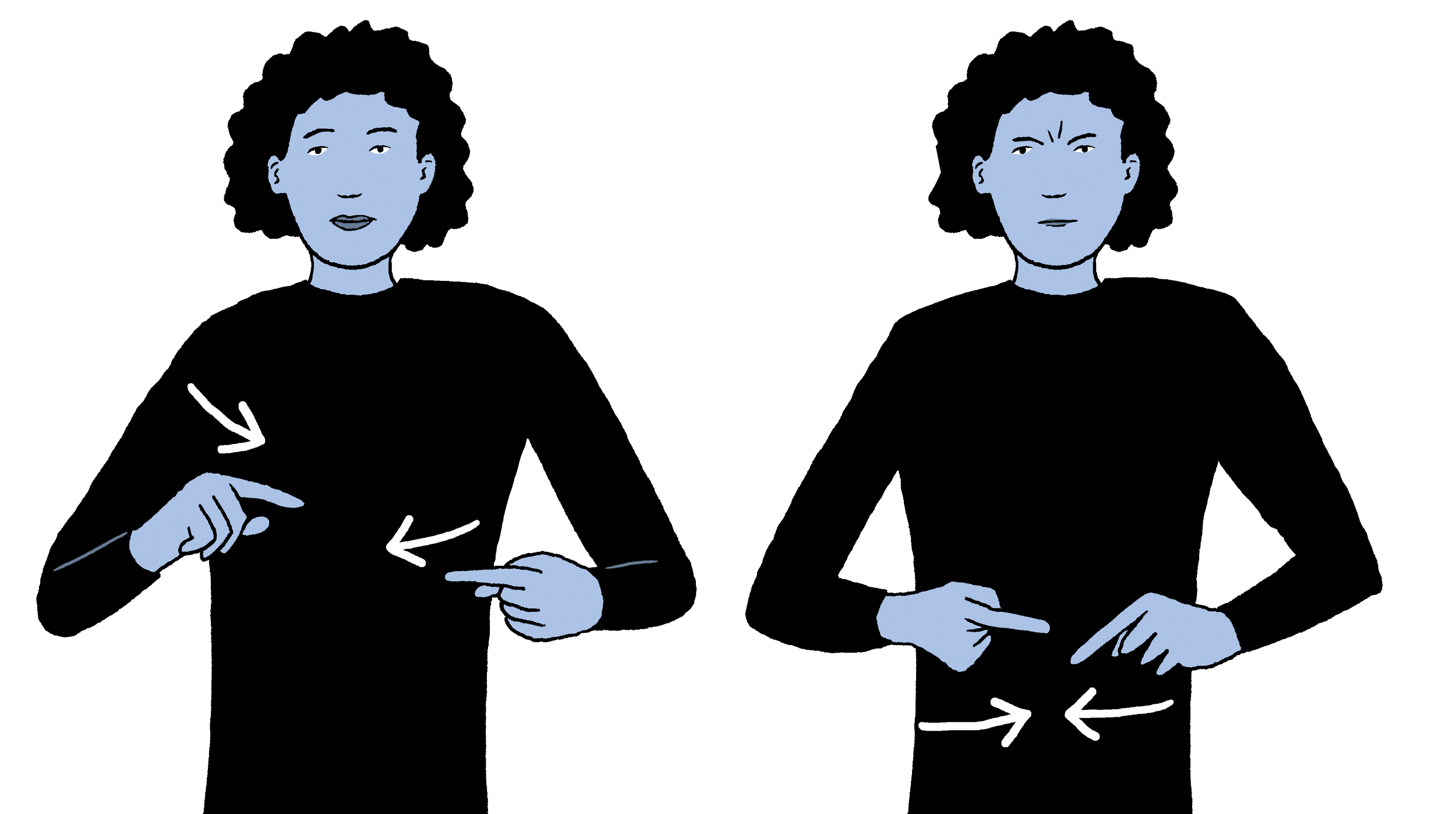

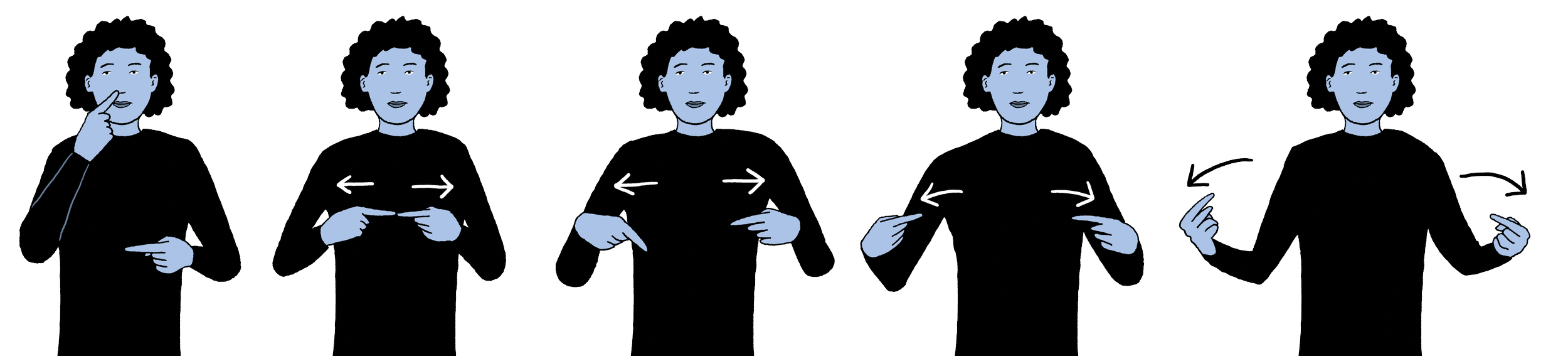

INTERPRETER

“I will never know what it is like to be deaf, but I do know what it’s like to be hospitalized,” says Michelle Litchman, an associate professor and family nurse practitioner in the College of Nursing, the medical director of the Intensive Diabetes Education Support Program, and a colleague of Rafeek. “It can be a very scary place to be.”

But imagine how that fear grows when you can see people having conversations around you, nurses bringing you medication, and doctors ordering tests; but you can’t hear any of it—or communicate your own wishes in the process.

When Rafeek headed home two days after entering the ED, she received discharge papers that helped her finally understand her diagnosis—written there in black and white: Type 2 diabetes. Her family doctor had told her two years earlier that she had pre-diabetes, but she admits today that she didn’t understand what that meant or what she had to do to get better.

DIFFICULTY BREATHING

More than 37 million people in the United States have diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. But it seems to hit the Deaf population particularly hard. According to Litchman, Deaf people are three times more likely to say they have diabetes.

“Diabetes is complicated no matter who you are or what language you speak,” says Litchman in a new short film from U of U Health called Language of Care, which made its debut at a sponsorship event during the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.

DEAF

Having grown up in a family with six Deaf members, Litchman was used to the complexities of treating Deaf patients long before she went into medicine—she was often brought along to appointments to interpret for her family. In fact, as a high school student, she was the one who had to tell her aunt that she wasn’t a good candidate for a cochlear implant. It was devastating news for her aunt to receive. She was once able to hear but had lost her hearing at age 11. It was devastating, too, to be the one to sign those words to a family member and crush her hopes.

“I had to be the bearer of bad news,” Litchman says.

She also had to receive it. When a different aunt was admitted to another hospital with a pulmonary infection, she didn’t come home. As a Deaf woman, she asked for an interpreter but was told she could only have one when her doctor did rounds. Alone in her room one day, she pushed her call button and signed to her nurse, “I can’t breathe.” Her nurse didn’t understand the sign, and it wasn’t until it was too late that the medical staff realized the issue. The infection had taken over, and she died as a result.

“When they denied my aunt that interpreter, she never had a chance,” Litchman says. “I knew it could have been prevented.”

When Deaf patients don’t have access to an interpreter, they are already behind in their own care. Some rely on lipreading, some on images or the written word, but patients’ understanding may vary depending on how well they interpret images or written messages in English. After all, American Sign Language is not, as most Americans wrongly assume, visual English. In fact, ASL has its own words, its own sentence structure—and much of the meaning of a sign comes not from the sign itself but from the expression on the signer’s face or the way they move their body. Add in the fact that the medical community employs its own terminology. ASL interpreters may not be trained in these medical terms, widening the communication gap between medical teams and their patients and causing largescale impacts.

“Deaf sign language users have lower health literacy and poorer access to non-communicable disease prevention information as compared to the general population,” according to a 2019 article in the Journal of Health Equity.

In short, Deaf patients are dealing with preventable issues more often than their hearing neighbors. “Don’t they say that health care is a fundamental right?” asks Litchman in Language of Care. “But for who?”

“I will never know what it is like to be deaf, but I do know what it’s like to be hospitalized.”

Michelle Litchman, PhD, FNPBC, FAANP, FADCES, FAAN, actively works to create a bridge between the medical community and their Deaf patients. Her efforts were featured in the docushort, Language of Care, which U of U Health premiered at a sponsorship event during the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.

When it comes to non-communicable disease, Litchman, who has studied diabetes and worked with people living with diabetes since 2006, is an expert. She had spent years researching how diabetes impacted families. She had worked to create better models for diabetes management. And she had focused specifically on technology and models that would better reach underrepresented populations. How could she use her connections to the Deaf community, her fluency in ASL, and her many years of research to help narrow the communication gap between Deaf patients and their care team? Her sister did it, after all, by using her skills as an artist in New York and Oklahoma to create opportunities for Deaf artists. Could Litchman do the same in her chosen field?

Litchman’s opportunity came in 2021 when she applied for the Betty Irene Moore Fellowship for Nurse Leaders and Innovators. Her goal was to create a bridge between the medical community and their Deaf patients. As a first step, Litchman and research associate at the time, Murdock Henderson, began assembling a community advisory board comprising members of the Deaf community from around the country. The group would meet online over the course of seven months to discuss the barriers that the patients were seeing in doctors’ offices and hospitals—and to offer advice on the best ways to break them down. One challenge was the lack of available in-person interpreters.

DIABETES

HURT/PAIN

Many interpreters join a patient and doctor virtually, and that interaction depends on working video and WiFi, not to mention that the patient— often very ill or injured—may be expected to hold the screen, process the information, and sign back. Another issue was interpreters’ lack of comfort with medical terminology and medical settings.

“The data indicates about one-third of interpreters are not comfortable interpreting in medical situations,” Litchman says. “Medical terms can be tough to translate without proper training.”

There is only one sign for “insulin,” for example, though it has two meanings in English: the insulin produced in the body and the insulin given to treat diabetes. Conceptually, this can be confusing.

The other challenge was the desire to have a program that was delivered directly in ASL, bypassing the interpreter. The result of those meetings was a program called Deaf Diabetes Can Together, which took the feedback from this advisory board and put it into action with educational materials for Deaf people facing diabetes. Separately, a glossary of diabetes terms in ASL has been developed and used to deliver a diabetes-focused training for interpreters. Litchman’s team is also providing education to clinicians about how to optimize care for Deaf populations.

ALLERGY

“[Our advisory board members] are driving what we do because they’re telling us what they need,” says Litchman in Language of Care. “They’re codesigning health care with us.”

The feedback Litchman and her team receive goes back to U of U Health, so researchers, psychologists, statisticians, and designers can create better educational materials for interpreters, as well as for patients—materials that rely heavily on pictures and

other visuals to assist in communication. As Litchman points out, “within the Deaf community, there are different races, ethnicities, and religions, so we’re also bridging cultural gaps.” Consider nutrition, for example, a major component of diabetes treatment. Education isn’t framed around one food culture but many different cultures.

The new health care model the team created is now reaching beyond the Deaf community and is being adapted for rural Spanish-speaking communities in Colorado. And Litchman is currently working to adapt it to the Pacific Islander community.

Litchman’s aunt doesn’t have the chance to benefit from the strides being made to break down language barriers in health care. But Tamiko Rafeek does. She is a member of the Deaf Diabetes Can Together advisory board and shares her story with the medical

community so they better understand the issues. Rafeek’s experiences, the experiences of other members of the board, and the work of Litchman and her team will save other lives by curbing preventable diseases in communities that simply lacked a bridge to their medical teams.

“What we’re learning is helping us build a new model of care for Deaf patients, one that can be replicated in underrepresented communities,” says Litchman in Language of Care. “I think my aunt would be so proud.”

Deaf Diabetes Can Together is a 10-week diabetes self-management program that is delivered directly in American Sign Language. To be referred to this program, please email DDCT@utah.edu.